Hidden Strings

Paola Paleari

Originally published in Vantage Point, 2022

Invisible Cities is a novel by Italo Calvino published in 1972. It takes place at the court of the Tartar sovereign Kublai Khan, to whom the Venetian traveller Marco Polo describes the many remote cities he has visited on his travels across the sovereign’s endless empire.

Kublai hears about the two-faced Eusapia, whose urbanistic structure perfectly reproduces its underground arrangement. About Leonia, the town that renews itself every day: every object is brand new here, just pulled out of the packaging. The rubbish keeps on accumulating on the sidewalks, waiting for the garbage trucks to pick it up. And, again, Isidora, with its wall where the elderly sit and watch the young go by; Zemrude, a city whose look depends on the visitor’s mood; and Adelma, where it is possible to rejoin with one’s dead relatives and friends.

Marco Polo’s accounts are thorough and detailed, and nonetheless ambiguous; in fact, these exotic cities exist only in the mind of the traveler, who forms and performs them through his words, sounds, and gestures. While listening to Polo’s stories, Khan constantly doubts whether they are a chronicle or the result of pure invention. The traveler, for example, never mentions his beloved hometown Venice among the fantastic places he claims to have visited. But when the emperor asks him to speak of it, he replies: “What else do you believe I have been talking to you about?”

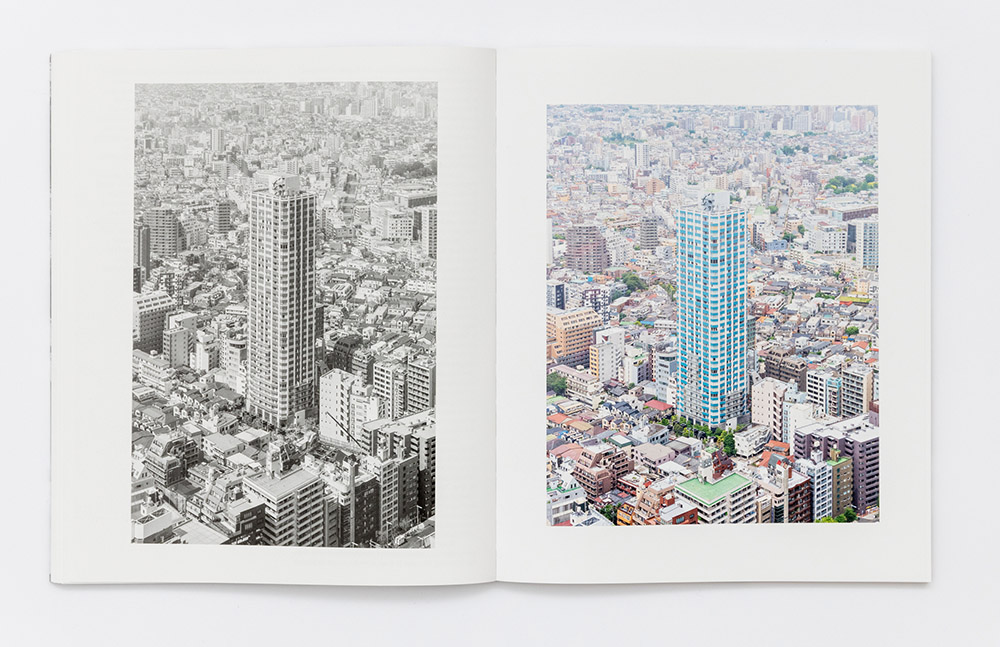

Like the real and all the same phantasmatic bride-of-the-sea, whose presence is invisible yet ubiquitous in Polo’s marvelous stories, the metropolis depicted by Daniel Everett and Mårten Lange in this book has the uncanny characteristic of being one, one thousand, and no city at the same time. The project started in 2016, when the two artists realized that they had photographed the exact same building in western Tokyo from the very same angle. The more they went through each other’s pictures, the more it became evident that that specific image pairing was not an isolated coincidence. On the contrary, several of their photographs—taken independently from each other and sometimes years apart—could be easily interchanged and mistaken as part of one single, coherent project.

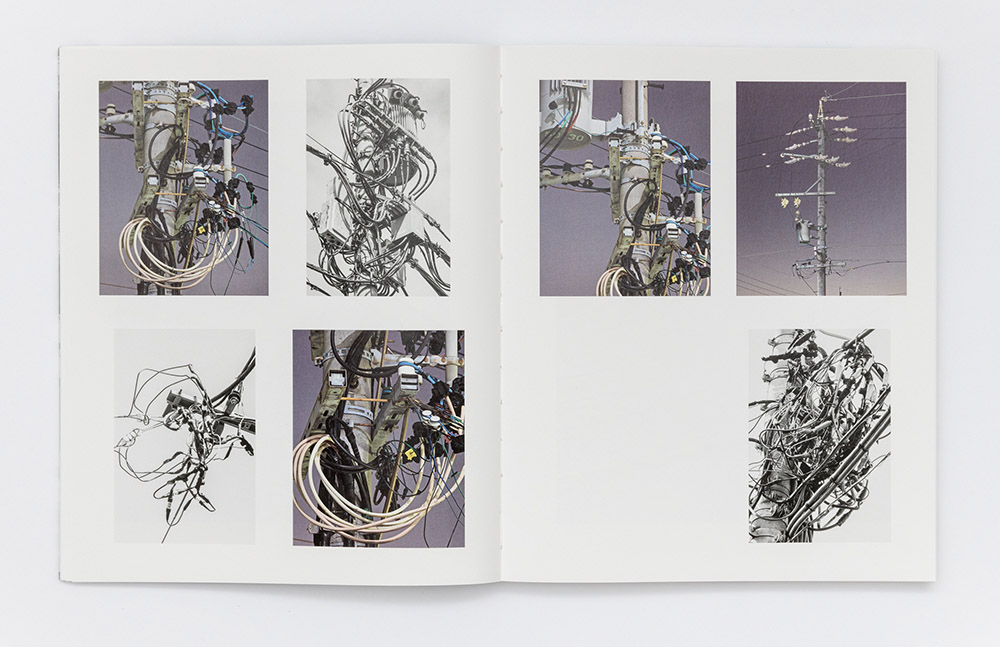

Even if sharing an unmistakable fascination for urban landscapes and the architecture of the megalopolis, the nearly perfect overlapping of choice in terms of subjects and framing angles initially surprised Everett and Lange. But on second thought, this synchronicity of the gaze revealed itself as not strange at all. In exploring the city through the lens, the two artists followed each their own interests and implemented their personal style. Nonetheless, they were attracted towards the same details and perspectives, almost if pulled by hidden strings stretched out by the city itself. Tokyo for Everett and Lange is like Venice for Polo: the supreme distillation of the idea of a city and the demonstration of its power on the life of inhabitants and visitors alike.

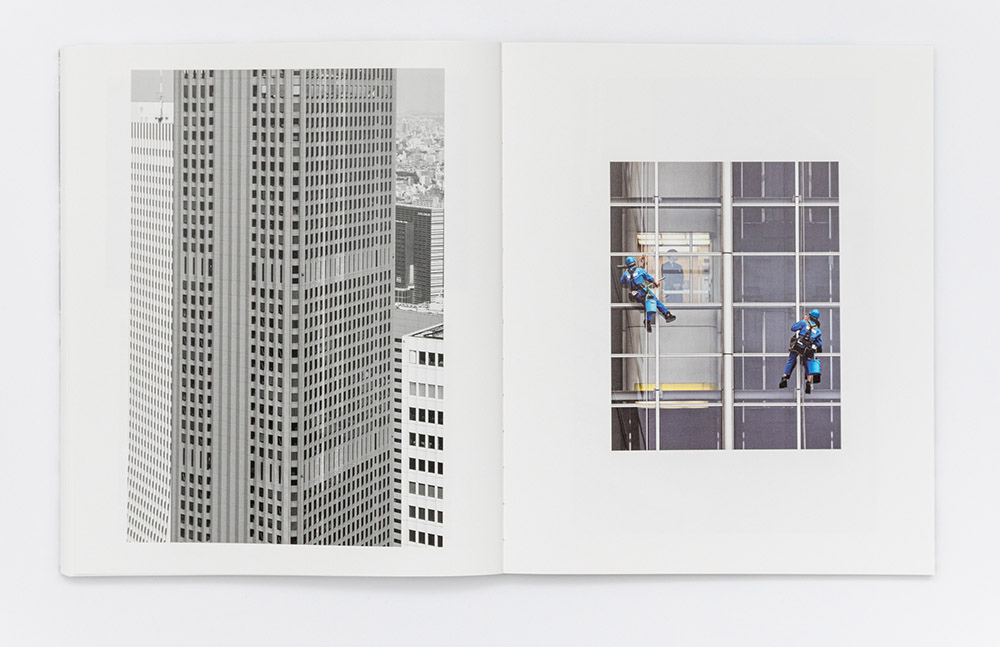

Maybe it is for this reason that, despite having spent lots of time in Tokyo, both artists still feel like aliens there. In global megacities, existence is a kaleidoscope of stories that flare ceaselessly within an architectural container, offering the ideal conditions for observing without being noticed. Photography—with its shared set of rules and formal principles on one side and its embedded lonesomeness on the other—can function as an optimal compass to navigate the bipolarity of presence and invisibility that characterizes the soul of the city. And precisely as a compass always points towards north, so did Everett and Lange find themselves looking in the same direction under the guidance of their photographic lenses.

Thinking historically, it might not be a fortuity that the first surviving photographs taken by Nicéphore Niépce in 1827 and Louis Daguerre in 1838 were street scenes, captured from the windows of their ateliers. Albeit the technical explanation for that is to be connected to the long exposure times and the odd size of the early cameras, which made it difficult to carry them around, it is hard to unsee a connection between the invention of photography and the start of modern urbanization. A connection that can be traced even further back in time, to the proto-photography of the view-painter Canaletto, who in the first half of the 18th century made use of the camera obscura to immortalize through his paintings the megacity of his times: Venice.

Another interesting parallel that can be drawn between Vantage Point and Invisible Cities is the relationship between the sender and the receiver of this spectacular portrait. It is a relationship that relies on trust and enchantment, where the objective truth holds a secondary place in the success of the narration. In their draw to organization and order (emphasized, complicated, or undercut through the images), Everett and Lange operate as the gateway to the overwhelmingness of the city. But just like the Great Khan in Calvino’s novel, the audience of this book has the possibility to transcend the accuracy of the description and get carried away in the experience of a meta-place that is larger than its topographic attributes and physical boundaries. The true spark of exoticism lies in the addition of our fantasies, desires and memories to the frame.

“’I think you recognize cities better on the atlas than when you visit them in person,’ the emperor says to Marco snapping the volume shut. And Polo answers, ‘Traveling, you realize that differences are lost: each city takes to resembling all cities, places exchange their form, order, distances, a shapeless dust cloud invades the continents.’”

Unlike an atlas, which fixes the external world by preserving the differences intact, Polo’s reports are a poetic attempt to reflect reality’s everchanging inner complexity. Similarly, Lange and Everett’s joint project aims towards an understanding of the manifold interactions intertwined between and behind the urban infrastructures. The authors see the city not as a static place, but rather as undergoing constant mutation and transformation—as a living organism with its needs, tics and internal metabolism. They present us with the reflection of this intricateness on the surface, and it is up to us to fully unfold it.